Netflix Italy

February 2018

Key Takeaways

Netflix did not launch in Italy until October 2015 and faced local market competition.

The Italian SVOD market is still small, especially if compared to the number of free-to-air and satellite/digital terrestrial television households, but it is slowly and constantly growing, and Netflix played a key role in this growth.

Netflix started its first national original production, debuting in October 2017 with the crime drama La serie, on the Roman connections between politics, religion and mafia. A documentary series on soccer team Juventus F.C. and a series called Baby will follow soon.

The Netflix brand, even before the launch, has been welcomed by consumers and national press with enthusiastic rhetoric, sometimes overestimating the strengths and revolutionary power of the service, leading to huge (and partially unrealistic) expectations on its success.

Market

Netflix entered the Italian market later than other major European countries (UK, France, Germany), on 22 October 2015 (together with Spain and Portugal). The service was already well-known in the country, thanks to its global hype and specific publicity efforts, and some people were already experimenting the service thanks to foreign accounts and VPNs. However, the strength of national “traditional” media and television, as well as the large number of players already established in the subscription-funded internet-distributed services arena (often explicitly offering a Netflix-like service before the official arrival of the service in Italy, with a large digital library of movies and TV shows), constituted important challenges for the global company, leading to the delay and strongly impacting its results.

Italy has a population of 60 million, and 24 million television households, which makes it an important, large-sized media market both in size and history. In particular, the media and television industries have been very rich and varied at least since the late 1970s and early 1980s, with the birth and consolidation of a strong commercial television operator, Fininvest (later Mediaset), able to launch foreign activities with varied success (in France, Germany and Spain) and to directly confront the national public service broadcaster Rai. As a result, to date, about 18 million households (data: IPSOS) watch only free-to-air, ad-funded television.

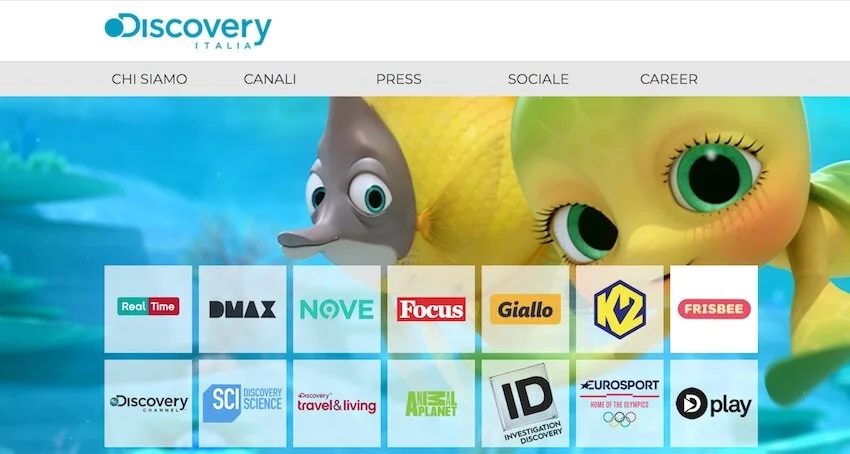

Free-to-air has found a new balance, with hundreds of channels and several newcomers, since the 2012 completion of the switch to digital terrestrial broadcasting. The public service broadcaster Rai still has a very important role, with three major channels and several digital ones, and with mainstream programming including entertainment, news, fiction, as well as movies and TV series. Silvio Berlusconi’s Mediaset has a symmetrical position in the commercial ad-funded landscape, with the other three major channels, several thematic and targeted ones, and a “generalist” approach to production and scheduling. Other players have also found a place in the free-to-air Italian market too: La7, a news and political talk-oriented network; Discovery, with a handful of targeted channels and an attempt towards mainstream programming (Nove); Sky, with free-to-air Tv8 (mainstream), Sky Tg24 (news) and Cielo (films, documentaries and TV series); and multinational conglomerates as Viacom, Sony or Turner play an increasing, yet small role, in a changing and expanding arena.

Almost 6 million households combine free-to-air television with subscriber-based satellite or digital terrestrial services. Also the Italian pay TV sector, after several attempts in the 1990s, found a new balance only in the following decade: in 2003, Sky Italia, part of News Corp., was established as a monopolistic satellite operator by merging two previous satellite services Telepiù and Stream; in 2005, a digital terrestrial, “low cost”, subscription service, operated by Mediaset and called Mediaset Premium, was launched too. Both platforms have their most important strength in the exclusivity of film and sports license rights, with football/soccer championships (national Serie A and Champions League) acting as the main driver; however, the offer includes many genres (US TV series, documentaries, factual entertainment, music, and so on) and has widened along the years to include (at least for Sky) original fiction (such as Gomorrah and The Young Pope) and light entertainment (with local X Factor, Got Talent and Masterchef editions). Sky has reached nearly 5 million subscribers, though its subscriber numbers appear to have plateaued. Mediaset Premium has around 1.8 million subscribers, but this number has been recently declining due to a reduced offer and on-demand competition.

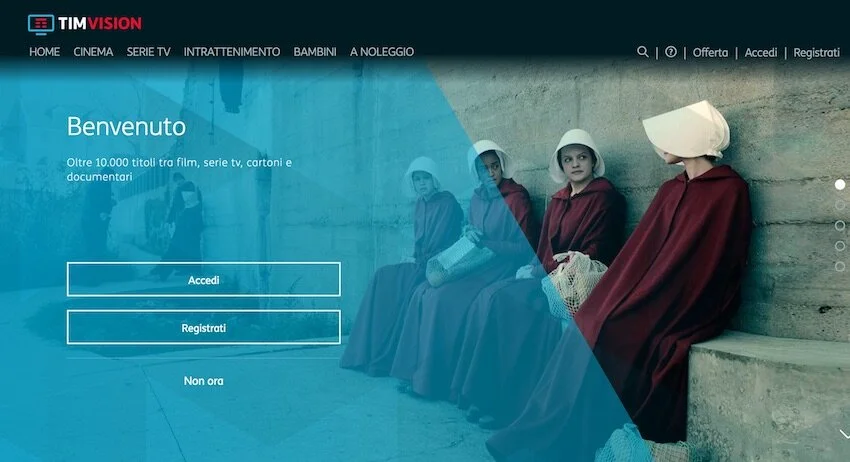

In such a complex ecosystem, many players experimented with some form of on-demand and/or internet-distributed television long before Netflix’s arrival—with different levels of success. Some telcos and internet-providers experimented with IPTV services, offering mostly classic movies and documentaries to a small number of tech-savvy early-adopters: Fastweb TV started in 2003 and terminated in 2012; Tiscali TV was launched in 2007 and closed in 2008; Infostrada TV rapidly followed in 2007 and closed in 2009. Landline and mobile operator Telecom Italia (later TIM) started Alice Home TV in 2005, then in 2016 rebranded and reformulated the service as a SVOD stand-alone platform called TIMvision, providing films, music, TV series, and even a number of Italian first-run exclusives (as the last seasons of Mad Men, and later The Handmaid’s Tale, Vikings and American Crime).

Subscription-based satellite and digital terrestrial operators have developed their own non-linear services as well. In a first phase, they were mostly conceived as a complementary service for their subscription base: Sky On Demand was launched in 2009, as well as Premium On Demand by Mediaset (later rebranded as Premium Net TV), both allowing time-shifted consumption of their linear channels’ programming; Sky Go and Premium Play both started in 2011, allowing outdoor and mobile viewing practices. Both companies are active too in the subscription-based internet-distributed segment with their stand-alone services: in December 2013, Mediaset launched Infinity, a streaming video service with no references to the company in its brand; a bit later, in April 2014, Sky Italia started its Sky Online no-strings-attached platform, later (following a global rebrand) called Now TV. Together with the emergence of many subscription-based services, the same years saw also the birth and the expansion of advertising-based free video on demand platforms, mainly operated by free-to-air television broadcasters – as Rai Play by Rai, VideoMediaset / Mediaset On Demand by Mediaset, DPlay by Discovery – and of transactional video on demand services – as Italian-based Chili, together with global large players like Apple iTunes Store, Google Play, Amazon, etc.

The entrance of Netflix in the Italian market was likely less successful than intended based on Reed Hasting’s enthusiastic announcements at launch, but it entered an already-dense field of historic media and television competitors strong in both production and distribution. Also, on a micro level, the established presence of at least three direct competitors – TIMvision, Infinity, and Now TV – strongly connected to national telcos and broadcasters which had implications for original content, license rights and promotional efforts. Despite this, within a few years Netflix was able to reach the largest share of the still small market of subscription-funded, internet-distributed television. This success has proven increasingly difficult for both other similar services and classic satellite and terrestrial subscription operators. In the last months of 2016, Amazon Prime Video began operations in Italy, and in 2017 phone and internet provider Vodafone started its own television service, called Vodafone TV.

Regulation

Although still characterized by uncertainty and fragmentation, Italian regulatory activity in the field of on demand audiovisual media services has recently undergone relevant changes, mostly aimed to harmonize non-linear and traditional media services by creating a common set of rules and, in the framework of the Digital Single Market Strategy, to sustain national and European production in an increasingly global market.

European legislative acts have had a key role in orienting the recent changes in Italian media law. Directive 2007/65/EC provided the first definition of “on demand audiovisual media services” in order to ensure a homogeneous and balanced competitive framework for both linear and non-linear media services. Italian Legislative Decree no. 44/2010 modified the pre-existing TUSMAR (Legislative Decree no. 177/2005 – Testo unico dei servizi di media audiovisivi e radiofonici) in order to put the Directive into effect and transfer to AGCOM (Italian Communications Regulatory Authority) the elaboration of the specific regulation about on demand audiovisual media services (Resolutions no. 66/09/CONS, 607/10/CONS and 188/11/CONS). With respect to obligations to promote European audiovisual productions, AGCOM requires 20 percent of European content included in the catalogue. Alternatively, a service can invest 5 percent of revenues of the previous year for European content acquisition or production. On demand services are due to reach these quotas in four years, and depending on market conditions.

This general framework is going to change again following the adoption of the Digital Single Market Strategy in Europe, with particular reference to the revision of Directive 2010/13/EU (Audiovisual Media Services). In order to sustain European production, the proposal “put on demand players under the obligation to promote European content to a limited level by imposing a minimum quota obligations (20 percent share of the audiovisual offer of their catalogues) and an obligation to give prominence to European works in their catalogues”, thus putting EU-produced content (without further specifications about nationality, at the moment) in the higher and most-visible positions in the interface. Moreover, member states have the power to impose a financial contribution for the production of European works and may impose fees on providers of on demand services in their territory, even if the providers are based in other member states. This measure is part of a wider process to improve jurisdiction rules and cooperation procedures with respect to the Country of origin principle (COO).

As far as Italy is concerned, these changes are going to be mainly regulated by Law no. 220/2016, which will govern the entire Italian audiovisual sector and represents the first structural intervention on the field since 1949. The Law also includes the revision of the system of obligations for linear and non-linear audiovisual media services, already established by Legislative Decree no. 44/2010 and the subsequent AGCOM Regulations. More particularly, the Legislative Decree ratified on 2 October 2017 (Decreto Franceschini) has already triggered a lively debate in the press, especially regarding programming and investment obligations for linear audiovisual media services. The Decree also introduces, in advance with respect to European legislation, programming and investment obligations for on demand audiovisual media service providers, although more detailed information is not yet available.

Other relevant regulatory areas include:

Rules for internet network operators (net neutrality). AGCOM carries out supervisory activities on the correct implementation of EU Regulation 2015/2120.

EU media law, cross-border portability of online content services and modernization of copyright rules (including cross border access to online content), as per the EU Digital Single Market policy.

Protection of IP and copyright enforcement. On 31 March 2014, a new Regulation on Copyright Protection in Electronic Communication Networks was introduced, following a lengthy development process and heated debate in the press.

Viewing Habits

Italian viewers are using a variety of devices to access Netflix and similar services, with both mobile platforms and “traditional” television sets playing important roles. According to the data provided by We Are Social and Hootsuite, in January 2017, 92% of the Italian adult population uses a TV set, 70 percent a smartphone, 63 percent a laptop or desktop computer, 31 percent a tablet, and only 6 percent a streaming device connected to television (e.g., dongle or set-top box). The same research shows how Italian internet users are accessing and displaying “television” content: 89 percent on a regular television set, 20 percent as recorded content on a television set, 10 percent as a catch-up or an on-demand service on a television set, 11 percent as online content streamed on a television set, and 13 percent as online content streamed on another device.

This diversity of viewing practices, with the television set still crucial and mobile device use growing, is confirmed also by the 2017 report of Osservatorio Social TV research at Università La Sapienza in Rome. According to this study, 37 percent of respondents are always/often using smartphones to watch television content (plus another 35 percent using them sometimes), while 21 percent are always/often using tablets to that extent (plus another 32 percent sometimes) and 39 percent are always/often using computers (plus another 45 percent sometimes). Television sets are preferred by a large margin, with 74 percent using them always or often to watch audiovisual content and another 20 percent using them sometimes. There are no specific data on dongles and decoders, which have a growing yet still very limited diffusion.

Internet Pricing and Availability

Italy has a moderate level of internet penetration (61.32 percent in 2016, according to the ITU statistics), with a constant growth of fixed broadband lines but a still low penetration rate of ultra-broadband services. The persistent and relevant gap between Northern-Central Italy and Southern Italy is being gradually reduced.

Based on the 2017 AGCOM Annual Report, in 2016 the increase in the number of subscription-based, internet-distributed services resulted in a growth of 40 percent (compared to 2015) of data traffic, amounting to approximately 12,400 Petabytes.

Based on the most recent data provided by AGCOM (September 2017) there are 20.58 million fixed access lines in a country of around 60.5 million inhabitants. Of these lines, 16.38 million are broadband and ultra-broadband. In percentage terms, according to the 2017 AGCOM Report, about 25.7 percent of the Italian population and 60.2 percent of households had access to fixed broadband services (> 10 Mbit/s). Only 3.8 percent of the population and 9 percent of households had access to fixed ultrabroadband services (> 30 Mbit/s). Geographically, there are still strong disparities in the diffusion of internet services, with a relevant gap between Northern-Central Italy and Southern Italy. However, a recent report points out that this situation is rapidly changing. In fact, in 2017 many Southern cities entered the top ten of the cities with the higher average download speed. The average download speed in Italy is currently about 15.91 Mbit/s (+ 67.7 percent compared to 2016).

As for the main Italian internet service providers, formerly state-owned and now national commercial operator TIM (Telecom Italia, which also offers the subscription-based non linear service called TIMVision) provides 60 percent of home internet service, followed by Vodafone (12.6 percent), WindTre (11.3 percent) and Fastweb (9.4 percent) (AGCOM). According to the Netflix ISP Speed Index, in September 2017 the best performance was offered by Vodafone (3.54 Mbit/s – fiber and DSL), followed by Fastweb (3.53) and then TIM (3,34). With respect to mobile networks, in 2016 the average monthly data traffic amounted to 1-76 Gigabyte per person (+ 33 percent compared to 2015) (AGCOM). There are 99.1 million of mobile subscribers, including human (83.9) and M2M (15.5) sim cards (AGCOM). WindTre is currently leader in the private customers market (AGCOM). The average monthly revenue per user (ARPU) for broadband connections go from 24 euros, for internet speed below 10 Mbit/s, and 42 euros, for internet speed over 30 Mbit/s. The average annual revenue per user for mobile connection range from 152 to 160 euros (AGCOM).

Netflix offers three kinds of package:

– 1 account/screen, standard definition, content download available on 1 tablet or smartphone: 7.99 euros per month;

– 2 accounts/screens, HD definitions, content download available on 2 tablets or smartphones: 9.99 euros per month (raised to 10.99 euros from October 2017);

– 4 accounts/screens, HD and Ultra HD definition, content download available on 4 tablets or smartphones: 11.99 euros per month (raised to 13,99 euros from October 2017).

Netflix pricing policies are generally well perceived by Italians. Only Amazon Prime Video, at the moment, has a lower price point, included in the annual Prime subscription along with free fast shipping (at 19,99 euros). Moreover, the informal practice of password sharing seems to be quite common: this practice needs to be further investigated in relation to the users’ perception of the value of the service and of Netflix’s popular recommendation system.

Content

As Netflix entered the Italian market, the huge difference in the number of titles between the Italian and the US catalogues was frequently emphasized by the Italian press. According to data provided by Finder.com in January 2016, the Italian catalogue offered 1000 movies and 196 TV shows, an extremely poor offering if compared to the 4579 films and 1081 TV shows of the US catalogue. Referring to Finder.com, the Italian catalogue offered a share of 22 percent of US movies and a share of 15 percent of US TV shows. More recent, unofficial estimates of Netflix’s Italian catalogue (Netflix Lovers) account for a total amount of 2717 items, although it is not possible to differentiate between movies and TV series (at the present, uNoGS provides no public data about the Italian catalogue). According to the “Italy Subscription OTT Focus Report” by Ampere Analysis, in September 2017 Netflix’s Italian catalogue reached 3187 titles, with 2189 movies and 998 TV seasons, thus surpassing the library width of each of its national competitors (including the former largest library, Mediaset Infinity).

Another partial estimate, limited to films, is offered by the EAO (European Audiovisual Observatory) report Origin of films and TV content in VOD catalogues in the EU & visibility of films on VOD services (November 2016). According to the report, the Netflix catalogue in Italy offers 1631 movies, of which 22 percent are of EU origin and 4 percent of Italian origin. US films represent 66 percent of the catalogue. Across all the Netflix catalogues in EU28 (6267 film titles), European movies represent on average 25%, while the share of national films is between 1 and 10 percent.

The abundance of TV series is commonly considered the most appealing aspect the Italian Netflix catalogue. Also, the possibility of binge-watching, the technical quality of the streaming, and the friendly and engaging interface are highly appreciated. Based on press coverage and social buzz, original productions such as Stranger Things, Narcos, Mindhunter or Orange Is the New Black are particularly popular. House of Cards is currently unavailable in Italy, since the rights had been previously sold to the subscriber-based satellite television Sky Italia. Sky, with its standalone SVOD service Now TV and its exclusive deals with HBO and Showtime, is currently the main competitor in the field of television shows, and offers many popular series such as Game of Thrones, True Detective and Westworld.

Competition between Sky and Netflix is also evident in the production and distribution of original, localized content. While Sky has already gained international success with Italian television shows like Gomorrah and The Young Pope (among others), Netflix has just released its first Italian production Suburra. La serie, coproduced by Cattleya and Rai Fiction. The next original Italian productions will be the docu-series Juventus FC and the series Baby, “a coming-of-age story that explores the unseen lives of Roman high schoolers” (produced by Fabula Pictures and written by a team of writers called “grams”).

Consumer and Press Reaction

There was considerable buzz around Netflix prior to its arrival in Italy. The brand enjoyed a continuous presence in Italian-language web pages, newspapers, and media from 2012, with detailed accounts of the platform’s features and its global-expansion plans, and rumours about a future debut in Italy, which intensified in the years that followed, and especially in the months of June-September 2015, leading up to the launch in October. The international discourse was first mediated by foreign correspondents in the US, framing it as a new curious “phenomenon” from abroad and a possible future revolution, and then explored in more detail by tech journalists, focusing on platform, interface and library, and by entertainment specialists as well, who scrutinized the content, original productions and the actors and writers involved. This sporadic yet constant presence received a boost with the first European expansion of the platform in 2012, with mixed feelings of exclusion from the first and second tier of countries involved and of hype on the brand and its main assets, waiting for the almost inevitable Italian “invasion”.

The first official announcement of the Netflix launch on the Italian media market came on Saturday, 6 June 2015. The carefully planned story was released through several media outlets, especially to reach the service’s potential target audience, mainly young viewers and tech-savvy early adopters. During the first months, Netflix was presented in the public discourse with growing enthusiasm and discussed as a global success story, a disruptor that could change television and frighten established broadcasters—a game-changer, a threat. Newspaper and magazine headlines, as well as social media buzz, reported that on-demand would destroy classic television, with its obsolete models and lowbrow shows, freeing viewers from the tyranny of the schedule, synchronized viewing times, and programming made only of entertainment formats. Media coverage focused on the strengths of the service: low price, ease of access, a user-friendly interface, excellent compatibility with many digital platforms, original content (already familiar to Italian viewers), and a choice of multiple versions of films and TV series (original, subtitled or dubbed in Italian). Some articles and comments also looked at weaknesses, often relating not directly to the service but to Italy’s media system and infrastructure in general: the patchy high-speed bandwidth coverage, the paucity of early adopters in an under-developed digital nation, the content library still under construction because of a lack of available licence rights, and the high competition in the market with the other services operated by broadcasters and telcos.

With the official launch of the service, on 22 October 2015, the enthusiastic rhetoric reached a peak, detailing all the promotional activities developed by Netflix communications and PR both on the press (including direct competitors) and in the grassroots discourse, and raising even higher expectations on the platform and its ability to disrupt the national media system. The struggle between the expectations, raised by the company and indirectly by all the consumer and press reactions, and the actual first few months of operation in Italy prompted a recalibration of the previous discourses, with a more varied, sometimes cynical and detached, online commentary and a “normalization” of Netflix’s presence on mainstream media. Attention now focused on the limitations extent of the local catalogue (in terms of films and national productions), on the obvious gaps in the catalogue (including global landmarks such as House of Cards), and on the inability to fulfil (impossible) requests like the availability of the new episodes of US network and cable TV series.

Later, with greater public understanding of the service and the library size slowly increasing, the discourse shifted from “exceptional” to “everyday”. Netflix is a part of the landscape, media coverage focused on new original productions (with advertising spots in national networks’ programming, and connections to Italian media events and personalities). The consumer and press attention is still very high, but the activities of Netflix and its brand are slowly becoming the object of a less enthusiastic, more nuanced and multi-faceted discourse.

Subscriber Estimates

Although no official data are available, there are some estimates provided by different research companies. According to a EY report in February 2017, subscriber-supported internet-distributed services had in Italy almost 1.5 million subscribers and over 3.7 million users; Netflix’s market share is steadily increasing, reaching around 35 percent of internet-distributed service subscribers and 0.6 million subscribers in the first months of 2017. The “Italy Subscription OTT Focus Report” by Ampere Analysis, out in September 2017, confirms this trend of moderate but continuous growth, establishing Netflix at around 0.8 million subscribers. Netflix has become the market leader by some extent, but the other global (Amazon) and local (TIMvision, Infinity, Now TV) competitors all have from 0.25 to 0.45 million subscribers each, resulting in a still very fragmented market. A comparison with digital terrestrial and satellite subscriber-supported television services (Sky Italia and Premium Mediaset), with almost 6 million subscribers, as well as with ad-based internet-distributed services (including YouTube, Rai Play, Mediaset On Demand or DPlay), with 14 million users, show well how Netflix’s and other similar services numbers are still relatively small in Italy.

Local Netflix Office

In Italy, there is no Netflix local office. A small number of Italian managers and employees work in the Netflix EMEA (Europe, Middle East and Africa) headquarters in Amsterdam, focusing on the national service or on larger regions. In Italy, MSL Group in Milan acts as a press office and PR house, coordinated by a Netflix publicity manager.

Suggested reading

Giorgio Avezzù, “The Data Don’t Speak for Themselves. The Humanity of VOD Recommender Systems”, in Cinéma&Cie. International Film Studies Journal, 29, 2017.

Luca Barra, “On Demand Isn’t Built in a Day: Promotional Rhetoric and the Challenges of Netflix’s Arrival in Italy”, in Cinéma&Cie. International Film Studies Journal, 29, 2017.

Luca Barra, Palinsesto. Storia e tecnica della programmazione televisiva. Rome-Bari: Laterza, 2015.

Luca Barra and Massimo Scaglioni, “Convergenze parallele. I broadcaster tra lineare e non lineare”, in Valentina Re (ed.), Streaming Media. Circolazione, distribuzione, accesso, Milan-Udine: Mimesis, 2017, pp. 31–47.

Stefano Baschiera, Francesco Di Chiara, Valentina Re (eds.), “Re-intermediation: Distribution, Online Access, and Gatekeeping in the Digital European Market”, special issue of Cinéma&Cie. International Film Studies Journal, 29, 2017.

Ester Corvi, Nuovo cinema web. Netflix, Hulu, Amazon: la rivoluzione va in scena. Milan: Hoepli, 2016.

Marco Cucco, “La rottura della clessidra. Le sfide del VOD alla filiera cinematografica e alle politiche pubbliche”, in Valentina Re (ed.), Streaming Media. Circolazione, distribuzione, accesso, Milan-Udine: Mimesis, 2017, pp. 73–88.

Giorgio Greppi, “Quadro normativo e regolamentare del video on demand in Italia”, in Valentina Re (ed.), Streaming Media. Circolazione, distribuzione, accesso, Milan-Udine: Mimesis, 2017, pp. 89–105.

Francesco Marrazzo, Effetto Netflix. Il nuovo paradigma televisivo. Milan: Egea, 2016.

Valentina Re (ed.), Streaming Media. Circolazione, distribuzione, accesso. Milan-Udine: Mimesis, 2017.

Valentina Re, “See what’s next. Continuità, rotture e prospettive nella distribuzione online”, in Valentina Re (ed.), Streaming Media. Circolazione, distribuzione, accesso, Milan-Udine: Mimesis, 2017, pp. 7–29.

Valentina Re, “Online Film Circulation, Copyright Enforcement and the Access to Culture. The Italian case”, in Journal of Italian Cinema & Media Studies, 3(3), June 2015, pp. 251-269.

Valentina Re, “Italy on Demand. Distribuzione online, copyright, accesso”, in Cinergie. Il cinema e le altre arti, 6, 2014, pp. 64-73.

Marica Spalletta, “Il fenomeno Netflix sulla stampa italiana”, in Valentina Re (ed.), Streaming Media. Circolazione, distribuzione, accesso, Milan-Udine: Mimesis, 2017, pp. 49–72.

Stefano Zuliani, Netflix in Italia e il big bang di cinema e tv. Milan: Il Sole 24 Ore, 2015.